CHAPTER IX

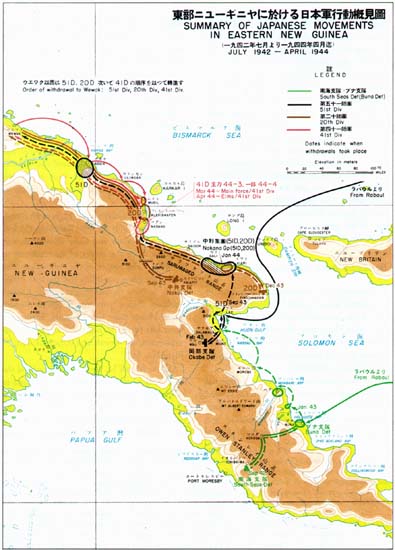

FIGHTING WITHDRAWAL TO WESTERN NEW GUINEA

Southeast Area Situation, June 1943

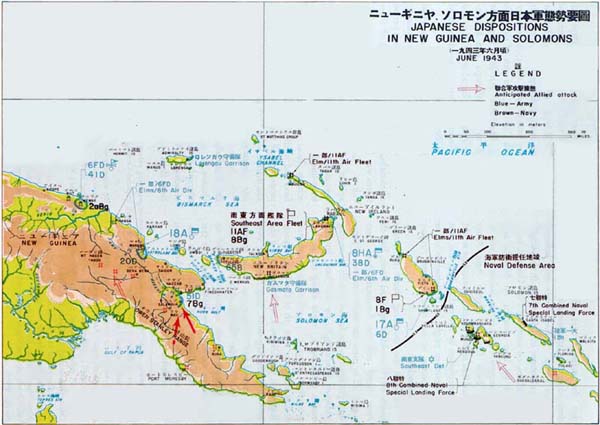

Despite steadily intensified efforts through April and May to strengthen Japanese defenses in New Guinea and the central Solomons in preparation for the next phase of hostilities, the strategic and tactical situation which confronted the Japanese command in the southeast area at the beginning of June 1943 remained distinctly unfavorable.1 (Plate No. 52)

All along a front of approximately 1,200 miles extending from Lae and Salamaua in Northeast New Guinea, through Tuluvu and Gasmata on New Britain, to Bougainville, New Georgia and Santa Isabel in the Solomons, Japanese forces were thinly spread and on the defensive. Reinforcement and supply of the critical points along this extended front were severely hampered by expanding enemy control of the air and sea.

By June it appeared probable that an Allied attack would not be long delayed. Eighth Area Army intelligence reports indicated that enemy forces, estimated at three to four divisions in eastern New Guinea and three divisions in the southern Solomons, were rapidly being made ready for a new offensive effort.

Air bases in the Buna area and on Guadalcanal were being improved and expanded. Enemy planes not only were intensifying their attacks on Lae-Salamaua and on Japanese supply shipping in rear-area ports, but were sowing mines in Japanese-held coastal waters in the Solomons and extending their patrol radius to within close proximity of the Equator.2 Enemy naval forces were boldly attacking Japanese outposts in the central Solomons, subjecting shore defenses to artillery bombardment.

On the New Guinea flank, the key Japanese positions at Lae and Salamaua, guarding the southern land approach to the Dampier Strait, were expected to be the next major objectives of General MacArthur's forces. These positions already were threatened by reinforced enemy troops in the Wau area directly to the southwest, and increasing enemy activity in this sector indicated the probability of an early attack on the outer defenses of Salamaua. At the same time, infiltration of enemy forces into the Bena Bena and Mt. Hagen areas far to the northwest, where they were developing airfields, created a serious potential menace to Japanese rear bases at Madang, Hansa and Wewak.3

In the central Solomons, it was estimated

[208]

that the enemy's next offensive would be directed against Japanese outposts in the New Georgia group. Allied forces were believed likely to attempt initial landings in the vicinity of Wickham, on southern New Georgia, to be followed by later assaults on Munda and Kolombangara. Both in the Solomons and in eastern New Guinea, Eighth Area Army estimated that enemy attack preparations would reach completion by the end of July and that major offensives might be launched in either or both sectors at any time between August and December.4

To meet the mounting threat of enemy attack on these widely separated fronts, Eighth Area Army and the Southeast Area Fleet continued to press the reinforcement of Japanese garrisons in the face of steadily increasing transport difficulties.5 By mid-June, landing barges operating by night along the coastal route from Rabaul had successfully transported to Lae the main strength of the 66th Infantry Regiment, 51st Division, while elements of the 80th Infantry Regiment, 20th Division, were being moved from Madang by similar means. The 65th Brigade, transferred to Rabaul from the Philippines, was meanwhile moved to Tuluvu, on western New Britain, and the 51st Transport Regiment, 51st Division, was dispatched to Manus Island, in the Admiralties, to begin construction of an airfield.

In the Solomons area, concurrent steps had been taken to reinforce the naval garrisons charged with defense of the New Georgia group. The 229th Infantry Regiment, 38th Division, two battalions of the 13th Infantry Regiment, 6th Division, and part of the 10th Independent Mountain Artillery Regiment were moved to New Georgia and Kolombangara, while the 3d battalion of the 23d Infantry Regiment, 6th Division, was dispatched to Rekata, on Santa Isabel.

Although substantial numbers of troops had thus been advanced to the forward areas by dint of slow but persevering effort over a period of months, the fighting effectiveness of these forces was inevitably reduced by logistic difficulties. Large-scale Allied air operations against supply lines severely cut down the amount of rations and forage reaching the front-line forces, necessitating urgent steps to achieve local self-sufficiency.6 Shortages of food and medical supplies swelled the average proportion of ineffectives due to malnutrition and disease to as high as 40 per cent in frontline combat units.7

Owing to new developments in the tactical situation facing the Eighteenth Army in New Guinea, in particular the build-up of enemy strength in the Wau area and the preparation of advance Allied air bases in the vicinity of Bena Bena and Mt. Hagen, Eighth Area Army

[209]

PLATE NO. 52

Japanese Dispositions in New Guinea and Solomons, June 1943

[210]

on 20 June made some revisions in its general operations plan of 12 April. By virtue of these revisions, missions allotted to the various forces under Area Army command were newly specified as follows:8

1. Eighteenth Army: To effect the rapid completion of strong defensive positions in the LaeSalamaua area; to prepare for a new offensive against enemy forces in the Wau sector; to plan operations for the capture of enemy airfields in the Bena Bena and Mt. Hagen areas; to hasten completion of airfields at Wewak and Hansa; and to speed up construction of the Madang-Lae road.

2. Seventeenth Army: To accelerate defensive preparations of the 6th Division on Bougainville.

3. 65th Brigade: To complete construction of the airfield at Tuluvu on Cape Gloucester.

4. 6th Air Division: To begin immediate attacks on the enemy airfields under construction in the Bena Bena and Mt. Hagen areas and on the already existing enemy airfield at Wau; to attack Buna and enemy small craft moving along the New Guinea coast.9

In collaboration with the Eighth Area Army's revised plan, the Southeast Area Fleet continued to allot a portion of the Eleventh Air Fleet's land-based aircraft to support army air operations in New Guinea, particularly against enemy surface transport and amphibious convoys. The major mission of the Eleventh Air Fleet, however, remained to conduct air operations in the Solomons area, operating both from Rabaul and from an advance base at Buin, on southern Bougainville.10 Ground defense of Munda, Kolombangara and Santa Isabel, in the central Solomons, was also a navy responsibility, the Eighth Fleet exercising operational command over both army and navy units garrisoned there.

The Eighteenth Army command at Madang, in compliance with the new Area Army plan, immediately took steps to speed operational preparations on the Lae-Salamaua front and simultaneously began formulating concrete plans for an attack against the enemy airfields in the Bena Bena and Mt. Hagen areas. On 23 June, when the Deputy Chief of Army General Staff visited Madang to confer with the Eighteenth Army Commander, a preliminary plan envisaging the start of operations against Bena Bena in September had been elaborated, and a request was submitted for the allotment of an additional division, plus supporting troops, to carry out the operation.11

Meanwhile, on the Mubo front southwest of Salamaua, Lt. Gen. Hidemitsu Nakano, 51st Division commander, had already initiated a local offensive designed to forestall apparent enemy plans for a move against the Japanese defenses. On 20 June the newly-arrived 66th Infantry Regiment launched a coordinated attack from Mubo toward Guadagasal, but soon ran into difficulties due to the unexpected strength of the enemy positions. Despite heavy casualties, the regiment penetrated the forward positions and, on the night of 20 June, entered the secondary enemy defense line, where severe hand-to-hand combat took place. Again, losses were so heavy due to enemy superiority in automatic weapons that, on 22 June, the

[211]

attack was called off on the verge of success, and the 66th Infantry retired to Mubo. Its short-lived offensive had cost about 200 men.12

Without sufficient power to strike a decisive blow at any point on the southeast area front, the Japanese forces could do little but brace themselves to meet impending Allied attack. That attack came a full month in advance of the critical period forecasted by Eighth Area Army headquarters.

On 30 June the Allied forces struck with a two-pronged offensive launched simultaneously against Salamaua, in New Guinea, and Rendova Island, in the central Solomons.13 By striking earlier than the Japanese command had anticipated and at both places simultaneously, the enemy not only achieved tactical surprise but again divided the Japanese effort, particularly forestalling the concentration of 6th Air Division and Eleventh Air Fleet strength at either point of attack.

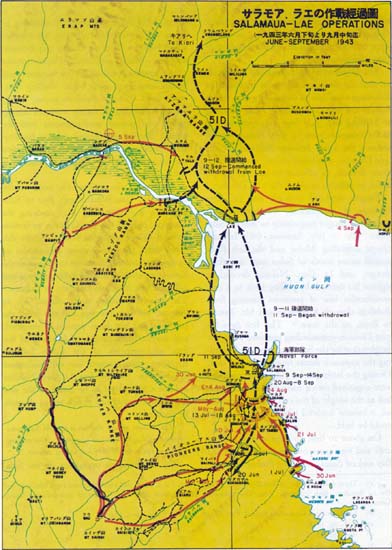

On the New Guinea front, the first wave of enemy troops, estimated at about 1,000, began landing at Nassau Bay, ten miles south of Salamaua, at 0330 on 30 June.14 (Plate No. 53) The suddenness of the attack caught the 51st Division forces guarding Salamaua off balance, with their main strength disposed to meet increasing enemy pressure on the Mubo and Bobdubi fronts, to the southwest and west of Salamaua. The only force in the immediate area of the enemy landing was the Nassau Garrison Unit, made up of the 3d Battalion, 102d Infantry Regiment, with a reduced strength of only a few hundred troops.15

After offering brief resistance to the first enemy elements put ashore, the Nassau Garrison Unit, on division orders, withdrew northward on 1 July, while the 3d Battalion, 66th Infantry was ordered forward to help stem the enemy advance from the beachhead. Meanwhile the 6th Air Division launched a series of attacks on the beachhead area, destroying or damaging a large number of enemy landing craft, although at the cost of relatively high plane losses.16 Despite these attacks, the enemy continued to put ashore additional troops and equipment.

Enemy forces now became active on the extreme right flank of the Salamaua defense perimeter, in the Bobdubi sector. To meet this simultaneous threat, Lt. Gen. Nakano ordered forward two battalions under command

[212]

of Maj. Gen. Chuichi Murotani, 51st Infantry Group Commander.17 This force, immediately upon its arrival at the front, was engaged in heavy fighting.

The Eighteenth Army command now decided that the decisive battle must be fought at Salamaua since loss of that base would render Lae, to the north, untenable. After returning to Madang on 7 July from an urgent air trip to the Salamaua front, Lt. Gen. Hatazo Adachi ordered the 238th Infantry Regiment of the 41st Division, which had moved up to Madang from Wewak, to advance to Lae via Finschhafen in order to reinforce the 51st Division.18

Despite depleted strength and an acute shortage of ammunition, the 51st Division meanwhile fought desperately to defend Salamaua. By 10 July, however, 66th Infantry troops defending Mubo and the left flank coastal sector north of Salus were in serious danger, and Lt. Gen. Nakano decided to tighten his defenses by pulling back to a new semicircular line of positions running from Bobdubi through Komiatum and Mt. Tambu to Boisi, on the coast.19 This line gave the 51st Division commanding positions along the heights skirting the Salamaua basin and guarding the approach routes from south and west. During the latter part of July, these positions were organized into a main line of resistance, but as the weight of the enemy assault increased, it became doubtful whether even this line could be held.

On about 20 July, 50 large enemy landing craft and four transports anchored in Nassau Bay and off Salus, indicating further reinforcements. The Allied troops began attacking in waves at close intervals, allowing the combatweary Japanese forces no time to rally between assaults. Mortar and artillery bombardment of the Japanese positions became incessant, and enemy long-range guns began shelling Salamaua itself. In the Bobdubi sector, enemy troops succeeding in taking scattered strongpoints and poured reinforcements into the gaps. The fighting entered a bitter hand-tohand phase, in which Japanese offensive action was limited to daring night infiltration raids behind the enemy lines.20

Alarmed at the unfavorable trend of the fighting, Lt. Gen. Adachi again flew to Salamaua on 2 August and, after studying the situation, ordered the 51st Division to further contract its over-extended front. Under this Army order, the 51st Division commander on 15 August ordered his troops to relinquish the Komiatum-Mt. Tambu-Boisi positions and fall back to a line from Bobdubi to Lokanu.21 The new dispositions were effected by 23 August, but the line was still too long, the positions had not been previously prepared, and despite the arrival from Madang of the first reinforcements of the 238th Infantry Regiment, troop strength was still inadequate at all points. Nevertheless, Lt. Gen. Nakano ordered a final stand to be made on the new line. In a message to troops on 24 August, he declared:

The mission of our division is to hold Salamaua without yielding a single foot of ground. Our existing positions constitute the very last line of defense. . . .22

The simultaneous operations on the Sala

[213]

PLATE NO. 53

Salamaua-Lae Operations, June-September 1943

[214]

maua front and in the central Solomons had meanwhile strained available Japanese air resources to the limit. Under an Eighth Area Army-Southeast Area Fleet joint agreement reached at Rabaul on 4 July, the 6th Air Division was used temporarily to strengthen the central Solomons area where a chance of a successful counterattack was foreseen. Combat losses and fatigue as a result of incessant activity seriously weakened the 6th Air Division, leaving no margin of strength for employment in the planned Bena Bena-Hagen operations.23

In mid-July, therefore, Imperial General Headquarters transferred the 7th Air Division from Ambon, in the Dutch East Indies, to the southeast area, and Fourth Air Army Headquarters was established to command all army air units operating under Eighth Area Army.24 First elements of the division arrived at Wewak on 25 July and, despite unfamiliarity with the New Guinea terrain, began operating immediately against enemy airfields in the Bena Bena-Hagen areas and the upper Markham Valley. After 1 August, however, in view of the greater urgency of the situation on the Salamaua front, the division shifted its primary effort to that area.25

The step-up of the Japanese air effort on the New Guinea front was not long in evoking severe enemy retaliation. On 17 August airfields in the Wewak-But area were subjected to a surprise attack by enemy aircraft, far surpassing in scale and intensity any previous air assaults.26 Destruction of 100 aircraft in this single attack cut down by more than half the total serviceable plane strength of the Fourth Air Army and rendered the enemy's margin of air superiority so decisive that all phases of the Japanese military effort in New Guinea were severely affected.27

On the Salamaua front, the loss of air support immediately resulting from the Wewak raid further compromised the already perilous position of the 51st Division. Enemy bombing and strafing of the Japanese positions intensi

[215]

fied, and movements of troops and supplies became virtually impossible.28 The 51st Division, now facing greatly superior enemy forces,29 nevertheless continued to hold stubbornly to its last defense line against continued heavy pressure on both right and left flanks.

Toward the end of August, this pressure slackened to some extent, and it appeared that the enemy had shifted his attention from Salamaua itself and was massing his strength in the Gabensis-Wampit area, west of Lae, with the objective of gaining control of the Markham Valley. This shift in direction of the Allied effort, coupled with a marked increase in the movement of surface transport off the eastern New Guinea coast to the south of the Huon Gulf, pointed to the strong probability that another amphibious operation was about to be set in motion without awaiting the final reduction of Salamaua.

During the latter part of August, Imperial General Headquarters closely studied the deteriorating situation on the New Guinea front and decided upon a new change in operational policy. It was now clear that there was scant hope of holding the Lae-Salamaua area for development as a future counteroffensive base. Therefore, on 30 August, a new Army-Navy Central Agreement was formulated, under the terms of which merely a holding action was to be fought at Lae and Salamaua to cover the establishment of new defense positions guarding the Dampier Strait. An Eighth Area Army order directing this change was transmitted to the Eighteenth Army on 2 September. Essential points of the local agreement were as follows:30

1. Units in the Lae-Salamaua area will meet the attacking enemy with present local strength and attempt a holding action. In the meantime, defenses in the Dampier Strait region will be quickly strengthened.

2. The Army and Navy will use every means available to insure supply and replacements to the Lae-Salamaua area. To this end, effort shall be made to provide at least an amount equal to August shipments.

3. If the situation makes it absolutely imperative, Army and Navy units in the area will be transferred to the rear at the opportune time. The Eighteenth Army commander will direct this operation and will endeavor to move his forces to the Finschhafen area.

4. The Army and Navy will station strong units on Umboi Island and on both coasts of the Dampier Strait insofar as supplies permit, thereby strengthening the defense of the strait and giving all possible protection to surface transportation in the area.

Before any concrete tactical plans could be drawn up to implement the new policy, however, the enemy launched his long-anticipated move against Lae. On 3 September Allied aircraft heavily attacked Lae and Cape Cretin on New Guinea, and Tuluvu and Rabaul on New Britain. On the morning of the following day, a large enemy convoy moved into Huon Gulf and, after devastating air and naval gunfire preparation, effected troop landings between Hopoi Mission and the mouth of the Busu River, about twenty miles east of Lae.

While the amphibious landings were in progress, enemy parachute troops were dropped near Nadzab, 20 miles west of Lae up the Markham Valley, on 5 September. As these two forces began converging on Lae from east and west, enemy troops on the right bank of the Markham River began advancing down

[216]

stream from Gabensis. The enemy's plan, now rapidly unfolding, appeared to aim at bottling up the defenders of Lae by a threeway assault and sea blockade.31

By 7 September it was estimated that one enemy division had been put ashore over the Huon Gulf beaches,32 while reports from the Markham Valley front indicated that large numbers of Allied transport planes were using the airstrip at Nadzab to ferry in reinforcements. On the basis of this air transport activity and the number of vessels at Buna, Nassau Bay and in Huon Gulf, it was estimated that the enemy buildup would approximate two divisions.

In view of the overwhelming superiority of the attacking forces and pursuant to the decision to fight merely a holding action in the Lae-Salamaua area, the Eighteenth Army Commander, Lt.Gen.Adachi, ordered the forces defending Lae and Salamaua to contract their lines and prepare for future retirement northward along the southern flank of the Finisterre Mountains and the Ramu River Valley, or through the Saruwaged Range if the former route could not be used. Evacuation of Salamaua was to be effected immediately.

Pursuant to the Army order, Lt. Gen. Nakano immediately proceeded to evacuate litter patients and heavy weapons to Lae by water. On the night of 6 September, one battalion of the 102d Infantry and Sasebo 5th Special Naval Landing Force were transferred to Lae by water to reinforce the extremely weak defense of the Lae area. It was imperative that the 51st Division hold the Lae area, at least temporarily, in order to secure its withdrawal route north. East of Lae, defensive positions were taken up along the Busu River. To the west, the enemy force advancing from Gabensis was heavily engaged near Markham Point, while the parachute and airborne troops pushing down the left bank of the Markham River from Nadzab were engaged at Yalu. Aware of the gravity of the situation, many officers and men left their beds at the Lae Field Hospital and joined their comrades at the front.

Meanwhile on 11 September the main body of the 51st Division began its withdrawal and, by 14 September, had closed on Lae.

Augmented by the troops withdrawn from Salamaua, Army and Navy forces in the Lae area now numbered approximately 9,085, including miscellaneous service elements. These troops, however, were in poor condition to conduct an effective defense. The units from Salamaua were battle-weary and understrength from nine weeks of continuous combat. The Lae garrison itself was weakened by a heavy proportion of ineffectives due to prolonged food shortages and sickness. Rations then available in the area were sufficient to last for about two weeks, and all outside supply had ceased with the enemy landings in the Hopoi area.33 Therefore, the 51st Division commander, now in command of all Army and Navy forces in the Lae area, prepared to withdraw the Lae forces to the north coast of the Huon Peninsula.

[217]

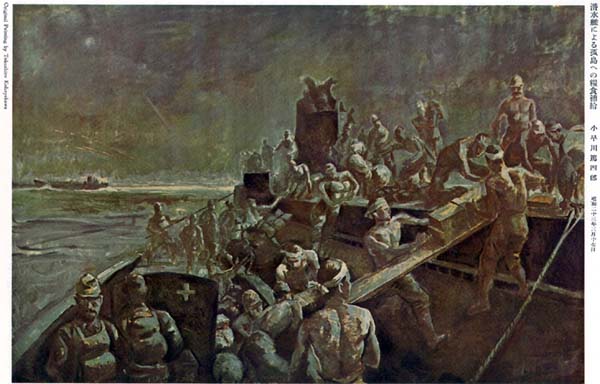

PLATE NO. 54

Navy Supplying Army Personnel by Submarine

[218]

Fighting in the Central Solomons

Concurrently with the Eighteenth Army's defense of the right flank bastion of the southeast area line at Lae-Salamaua, Japanese forces on the extreme left flank strove to parry the twin Allied thrust into the central Solomons.

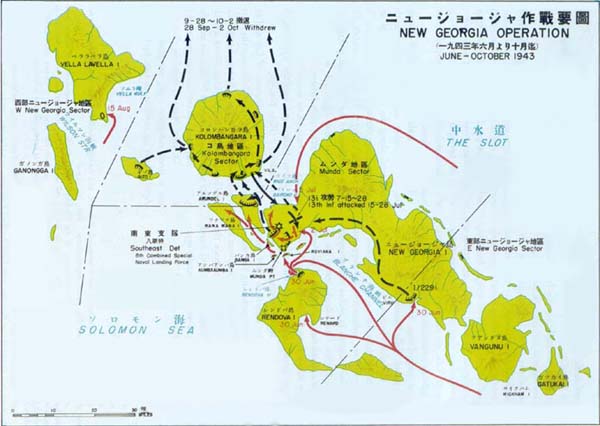

As a result of the crippling sea, air and ground losses suffered in the Guadalcanal campaign, general operational policy for the Solomons area had been modified in favor of defensive, delaying tactics designed to hold up the enemy's advance on the key Japanese base at Rabaul.34 The southeast area command anticipated that the next Allied blow would fall against the weak Japanese defenses in the New Georgia area, and after April efforts were redoubled to reinforce these defenses as far as transport facilities permitted.35

As in New Guinea, August-December was estimated as the critical period during which the Allies might begin a new offensive. However, in June, there was a sharp increase in enemy activity. Aircraft persistently conducted lowaltitude reconnaissance and photographic missions throughout the Solomons. Japanese shore defenses on Munda and Kolombangara were subjected to severe air and naval bombardment attacks, and powerful enemy fleet units were observed moving in the waters west of Guadalcanal.

Although these signs pointed to a possible attack earlier than previously estimated, it was difficult to forecast the exact spot at which the enemy would strike. Wickham anchorage, on the southeastern tip of New Georgia Island, continued to be regarded as the most probable point of attack. Therefore, when an enemy invasion force of six transports and escorting surface units suddenly began landing operations on Rendova Island, west of New Georgia, on 30 June, almost complete tactical surprise was achieved.36 (Plate No. 55)

Only Japanese troops on Rendova were a

[219]

small security detachment, which was swiftly overwhelmed and annihilated. Meanwhile, naval air units immediately launched repeated attacks on the enemy beachhead and invasion shipping with 106 aircraft, but encountered such strong opposing air cover that plane losses became prohibitive. Additional enemy troops were put ashore on 1 July, and on 2 July American heavy artillery emplaced on Rendova began shelling Munda airfield, on New Georgia.

In complete control of Rendova, the enemy proceeded to dispatch small amphibious forces to the nearby islands of Roviana and Aumbaaumba, lying in the narrow channel between Rendova and Munda, and followed up almost immediately by moving an advance force across Roviana Lagoon to land on the mainland of New Georgia. On 2 July, realizing that a major enemy offensive was in the making, the Southeast Detachment and the 8th Combined Special Naval Landing Force concluded a joint local agreement placing all army and navy ground forces defending Munda under operational command of Maj. Gen. Minoru Sasaki, Southeast Detachment commander.37

While Maj. Gen. Sasaki took initial steps to bolster Munda's defenses,38 another step in the Allied invasion plan unfolded. On 4 July enemy marines landed at Rice Anchorage on the northwest coast of New Georgia, about 15 miles from Munda, and before resistance could be organized, drove swiftly to the vicinity of Bairoko on 10 July.39 With Munda thus threatened from two directions, Maj. Gen. Sasaki decided to make the main defensive effort on the right flank. The 2d Battalion, 45th Infantry Regiment, newly arrived from Bougainville, was ordered to Bairoko to fight a holding action against the marines. Meanwhile, the 13th Infantry was moved forward from Kolombangara to Munda to bolster the main line already defended by elements of the 229th Infantry.

On 15 July the Southeast Detachment forces launched a coordinated attack on the Munda front in an attempt to turn the enemy flank, but repeated assaults failed to make headway, and the attack ended in failure. Thereafter, tightening enemy control of the air and sea made it increasingly difficult to move in reinforcements even from nearby Kolombangara,40 and the fighting power of the Japanese forces steadily declined under heavy attack by American aircraft, artillery and armor. By 31 July, the units defending Munda airfield were standing on their final defense line.

In view of the evident hopelessness of continued resistance on New Georgia, Maj. Gen. Sasaki on 7 August ordered the gradual withdrawal of the forces defending Munda to Kolombangara. The 13th Infantry, covered by rearguard actions fought first at Munda and then on Baanga Island,41 successfully effected its withdrawal. On the left flank around Bairoko, fighting continued until 19 August, when the 2d Battalion, 45th Infantry finally

[220]

evacuated to Kolombangara, thence moving on to Gizo Island.42

The main strength of the New Georgia defenders was now added to the forces available for the defense of Kolombangara, and Maj. Gen. Sasaki began an immediate reorganization of his troops with a view to launching an early counteroffensive. American troops, however, were already on Arundel Island, just across a narrow, mile-wide channel from the main Japanese base at Vila, on southern Kolombangara. While fighting continued there and on Baanga, an enemy amphibious force on 15 August suddenly seized Vella Lavella Island, 17 miles northwest of Kolombangara,43 thus threatening the Japanese defenses from a new direction.

In view of these unfavorable developments in the tactical situation as well as critical supply difficulties, Eighth Fleet Headquarters on 15 September ordered the evacuation of all Army and Navy forces from Kolombangara.44 The withdrawal operation was begun immediately, with barges and destroyers serving as the chief means of transport. American fleet units, which were then actively patrolling the waters west of the island, subjected the movement to extreme danger, but despite this menace the bulk of the Southeast Detachment and naval forces on Kolombangara were successfully evacuated to Bougainville and Rabaul.45

Evacuation of Lae and Ramu Valley Operations

At the same time that the Japanese forces were preparing to withdraw from Kolombangara, marking the end of the campaign in the central Solomons, the 51st Division and attached forces on the distant New Guinea front were pulling out of the besieged Lae area on the first stage of a difficult and costly retreat toward the north coast of the Huon Peninsula.

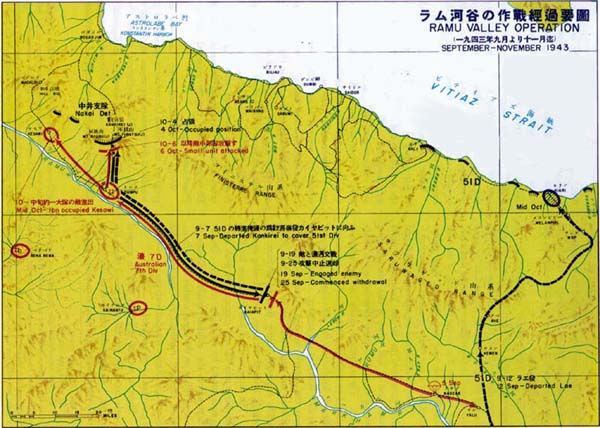

The Eighteenth Army plan had directed the 51st Division commander to route the withdrawal along the southern slopes of the Finisterre range, through Kaiapit, and into the upper Ramu Valley.46 To cover the withdrawal, a force composed of the 78th Infantry Regiment (reinf.), under the command of Maj. Gen. Masutaro Nakai, 20th Infantry Group Commander, was ordered to launch operations up the Ramu Valley and into the upper Markham Valley.47 (Plate No. 56)

However, the situation west of Lae and the open terrain made it impossible to use the Ramu Valley withdrawal route. Enemy forces occupied both banks of the Markham River, and the units which had landed at Nadzab on and after 5 September were squarely astride the road of escape. Lt. Gen. Nakano therefore elected to use a steep mountain trail, reconnoitered in April, which led north from Lae, up the Busu

[221]

PLATE NO. 55

New Georgia Operation, June-October 1943

[222]

PLATE NO. 56

Ramu Valley Operation, November 1943

[223]

River Valley, and then ascended the precipitous and dangerous Saruwaged Range. The initial objective was Kiari, on the north coast of the Huon Peninsula.

The Lae forces began evacuating on 12 September, and although the disengagement was rendered difficult by enemy attacks, the last unit of the 51st Division cleared Lae by early morning of 16 September. Materiel that could not be taken due to the condition of the trail was destroyed, and only rations, light equipment and a few heavy weapons were carried.

The first echelon of the retreating forces had only proceeded as far as Yalu, nine miles northwest of Lae, when it was attacked by a strong Australian force operating out of Nadzab. The withdrawal route had to be hastily altered to avoid the Yalu vicinity, and enemy aircraft heightened the difficulty of movement by daily bombing and strafing. After negotiating the densely wooded Atzere Range, the column was again held up at the Busu River while engineers, using timber cut from the jungle, bridged the deep, swift-running stream.

The route now led into limestone foothills, heavily timbered and interspersed with deep gorges carved by mountain streams. On 25 September, the column reached Kemen, a native village on the upper reaches of the Busu. Here the trail mounted into the formidable Saruwaged Range studded with peaks towering 13,000 feet above sea level.

Short of rations and clad only in tropical battle dress, the 51st Division troops began the ascent. At night the cold was so intense that sleep was almost impossible, even with a blazing fire. Each soldier had left Lae with only two weeks rations. These were exhausted before the division was well into the mountains, and the weakened troops had to negotiate the lofty Saruwaged Range on a diet of potatoes and grass.48 After the descent from the mountains into the steaming valley of the Kwama River, the retreating troops obtained some rations, which had been brought up the trail from Kiari by other units, but now tropical fevers took an increased toll.

What remained of the first echelon arrived in Kiari on 5 October, and by the middle of the month the concentration of the main body was completed. Wounds, dysentery, malaria, and malnutrition had claimed almost 2,600 lives. Those who survived were barely fit for duty, and practically all artillery pieces and heavy weapons had been destroyed during the retreat to prevent their falling into enemy hands. Under these circumstances, rest, reorganization, and refitting were urgently needed. However, only part of the division was ordered to proceed immediately to a rest camp at Bogia Harbor, near Hansa Bay, while the remainder was dispersed along the coast between Sio and Gali to guard the rear of the 20th Division, already heavily engaged in the Finschhafen area.49

While the withdrawal from Lae was in progress, the Nakai Detachment carried out its scheduled diversionary operations in the upper Ramu Valley. The detachment started out from the military road terminus at Kankirei50 on 12 September with the objective of seizing Kaiapit and then advancing into the Markham

[224]

Valley. Encountering no enemy opposition on the upper Ramu, the detachment advance guard reached Kaiapit on 18 September. There it encountered an Australian force in unexpected strength operating from the lower Markham in the direction of Kainantu. During the early morning of 18-19 September, the detachment attacked but failed to dislodge the Australians from their positions, and Kaiapit remained in enemy hands.51

At this juncture, important changes in the general tactical situation resulted in a revision of plans. Since the 51st Division was not retiring along its originally scheduled route, the Eighteenth Army Commander decided that it would serve little purpose to keep the Nakai Detachment on the offensive in the Kaiapit area. More vital, the enemy landing at Finschhafen on 22 September made it imperative for Eighteenth Army to shorten its lines and prepare to defend the important Madang base. With virtually no reserves available in that vicinity, Lt. Gen. Adachi decided to pull back the Nakai Detachment and hold it in strategic positions for the defense of Madang.

The detachment was therefore ordered to withdraw immediately to Dumpu and establish strongpoints in the vicinity of Kankirei and Hill 910. Its mission was to prevent the enemy from entering the Mintjim Valley corridor leading to Madang, and near conduct local counterattacks against enemy units advancing through the grasslands of the upper Ramu. The detachment's retirement near Dumpu was completed by 5 October. Enemy troops followed close behind and, on 6 October, launched an attack on Dumpu, successfully infiltrating some of the detachment advance positions. Lt. Gen. Adachi, visiting the front at this time, ordered the detachment to begin immediately its displacement to the previously selected positions at Kankirei and Hill 910.

Although these positions gave the detachment command of the main approaches to Madang, the Eighteenth Army Commander also became concerned over the possibility that the enemy forces from the Ramu Valley might slip around the detachment's left flank and penetrate to the coast, either across the Finisterre Range and into the valley of the Nankina River leading to Saidor, or into the upper reaches of the Kabenau River leading to Konstantin Harbor. Either eventuality would seriously endanger Madang. Consequently, small elements of the detachment were ordered up the Nankina and Kabenau Rivers to block these avenues of approach.52

Meanwhile, the enemy forces in front of the Kankirei and Hill 910 positions staged sporadic, small-scale attacks, which were successfully repulsed. The threat to Madang appeared at least temporarily ended.

The steadily quickening succession of reverses to which Japanese arms had been subjected during 1943 on virtually every sector of the farflung Pacific front finally culminated, at the end of September, in a sweeping and fundamental revision of Imperial General Headquarters' long-range strategy for operations in the Pacific theater.

The setbacks sustained in General MacArthur's area were a major factor in precipitating this decision. The initial losses of Guadalcanal in the Solomons and Buna-Gona on New Guinea, though considered serious, had not been regarded by Imperial General Headquarters as irretrievable. However, the subsequent loss, within the space of a few months, of the vital Lae-Salamaua area as well as

[225]

major Japanese strategic outposts in the Central Solomons, forcibly impressed upon the High Command that the southeast area was not being subjected to a more harassing or secondary attack. General MacArthur's objective was now recognized as the complete disintegration of the Japanese position south of the Mandated Islands.

Developments on other sectors of the Pacific front also influenced the shift in Imperial General Headquarters strategy. In the North Pacific, Japanese troops had been forced to evacuate Kiska in July. In the Central Pacific, a powerful attack had been carried out by American carrier aviation against Marcus Island, 1,100 miles from Tokyo. Wake, Kwajalein, Majuro and other key Japanese-held islands in the Marshalls were also struck, and American shipping was moving through the water of the Ellis Archipelago. Thus, a new enemy thrust appeared imminent in the Central Pacific parallelling the MacArthur drive from the southeast area.

In view of these major threats and Japan's declining military and naval strength, solidification of the inner defenses of the Empire had become imperative. Imperial General Headquarters, in particular, was aware that the national strength was no longer adequate to conduct operations in the southeast area on a large scale, and that Japanese troops must in the future avoid the terrific drain involved in constantly pitting weak ground contingents against stronger, better-equipped and more adequately supplied enemy forces. The swift buildup of decisive enemy superiority in the air also underlined the folly of such operations.

Moved by these considerations, the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters had for some time urged that a strategic line delineating Japan's "absolute zone of national defense" be fixed, behind the periphery of which air and ground strength could be replenished and marshalled for decisive battle. If this meant excluding the southeast area bastion of Rabaul, now almost in the front line, the Army stood ready to draw the perimeter line west of that locality.53

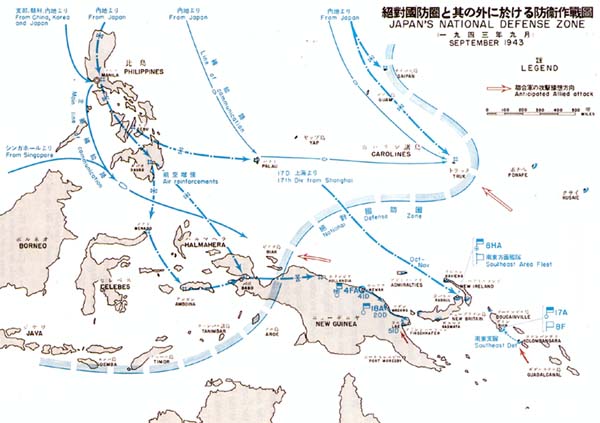

Of such fundamental importance was the decision on this issue that, on 30 September, the fourth Imperial Conference held since the start of the war was convoked to sanction the agreement finally reached between the Army and Navy.54 Under this agreement, the perimeter delimiting the absolute defense zone was drawn from Western New Guinea to the Mariana Islands via the Carolines. (Plate No. 57) This perimeter was to be strongly manned and fortified so as to deny the enemy further gains and to provide a bastion behind which forces could be gathered for offensive blows. Defense preparations behind that line were to be completed by the spring of 1944.55

The positions held by the Eighth Area Army and Southeast Area Fleet in Northeast New Guinea, the Bismarcks, and the Northern Solomons now constituted the outpost line in the southeast area, while the Second Area Army was to be transferred to New Guinea to take charge of operations along and behind the new national defense zone in Western New Guinea. Imperial General Headquarters clearly recognized the necessity of vigorously maintaining the outposts and holding the enemy at bay

[226]

PLATE NO. 57

Japan's National Defense Zone, September 1943

[227]

positions to the west were being prepared. With this in mind, the 17th Division was dispatched from Shanghai to Rabaul to reinforce the troops manning the forward wall.

On the basis of Imperial General Headquarters directives, Eighth Area Army revised its operational plans. General Imamura and his staff were of the opinion that the soundest tactics to accomplish the Area Army's mission of strategic delay were to conduct determined counterattacks against all Allied attempts to pierce the outpost line. The major critical areas to be defended were the Dampier Strait region, particularly Finschhafen and Cape Gloucester, and Bougainville in the northern Solomons.

Within the framework of the Area Army plans, instructions were issued to the subordinate commands. The Eighteenth Army in New Guinea was ordered to occupy and defend a line along the Finisterre Range, with emphasis on the Dampier Strait coast near Finschhafen. In order to cover the right flank and assist in the main mission of guarding the west coast of the Dampier Strait, a strong force was to operate in the Ramu Valley, and all enemy attempts to cross the Finisterre Range were to be repelled. The 51st Division was to retire west of Madang and continue its reorganization.

On New Britain, the Matsuda Detachment (65th Brigade, reinf.) operating under Area Army control was charged with strengthening the eastern defenses of the Dampier Strait, particularly Umboi Island and Cape Gloucester.56 The airfields at Gasmata, on southern New Britain, and on Los Negros Island in the Admiralties were garrisoned with smaller detachments, whose mission was to destroy enemy landings aimed at seizing the airfields.

On the left flank in the Solomons, the Seventeenth Army was being strengthened for the defense of Bougainville. The chief units stationed there were the 6th Division and the 4th South Seas Garrison Unit,57 while part of the 17th Division, was to come under Seventeenth Army control upon its arrival from China. The 38th Division was in the Rabaul area and on New Ireland.58

At this time the Fourth Air Army, consisting mainly of the 6th and 7th Air Divisions, was operating from widely scattered bases, mainly in Eighteenth Army territory. It was now ordered to operate principally from bases between Madang and Hollandia in support of planned operations. Eighteenth Army and the 65th Brigade were to have priority in calling for air support, and the primary mission was to destroy all enemy landing attempts in the Dampier Strait region.59

In support of Army operations along the outpost line, the Southeast Area Fleet planned to utilize available surface and air strength to disrupt enemy convoys en route to landing areas, while supply to the Dampier Strait region was to be assured by the use of submarines. Naval ground forces were also to be disposed at important points along supply and transport routes to insure the smooth functioning of shore activities such as communications, stevedoring, repair, and base defense.60

Even before detailed plans for the new dis

[228]

positions were completed, however, the enemy made an initial breach in the outpost line by an assault on the Finschhafen area.

Dampier Strait Defense: Finschhafen

Ever since the initial Japanese advance into eastern New Guinea, the 60 mile wide Dampier Strait lying between the western tip of New Britain and the Huon Peninsula had been of vital importance to Japanese sea communications between the main southeast area base at Rabaul and the New Guinea fighting front. The majority of troop and supply convoys dispatched to Buna and subsequently to the Lae-Salamaua area had moved via this narrow sea passage, and as General MacArthur's forces pressed northward, it was apparent that control of the strait would be a major Allied strategic objective in order to pave the way for further amphibious moves toward Western New Guinea.

Finschhafen, commanding the strait from the west, was the key point in the Japanese scheme of defense. Prior to the loss of Lae and Salamaua, troops moving forward from Rabaul and Madang had usually been routed through Finschhafen, which served as a stopping point and staging area. One of the best developed localities in New Guinea, the town controlled an area containing two excellent anchorages Finschhafen itself and Langemak Bay.

While the battle for Salamaua was still in progress, the Eighteenth Army commander foresaw the danger of an attack on the Finschhafen area and took steps to reinforce the weak garrison forces, which then consisted only of a small number of naval landing troops, some army shipping units, and groups of replacements destined for Lae. Army units in the area were under command of Maj. Gen. Eizo Yamada, 1st Shipping Group commander.

To strengthen these inadequate forces, Eighteenth Army on 7 August ordered the main strength of the 80th Infantry Regiment,61 20th Division, and one battalion of the 26th Field Artillery Regiment to proceed from Madang to Finschhafen. Subsequently, on 26 August, the 2d Battalion of the 238th Infantry Regiment, 41st Division, which had already advanced to Finschhafen on its way to Lae to reinforce the 51st Division, was ordered to remain at Finschhafen under Maj. Gen. Yamada's command.62 The Army forces in the area were assigned the mission of reconnoitering and organizing the ground in preparation for a possible enemy landing.63 Defensive organization of the coastal areas around the mouths of the Mongi, Logaweng, and Bubui Rivers and on Point Arndt was undertaken by Army units, while the naval garrison of about 500 men was given responsibility for the defense of Finschhafen proper.64

The enemy attack against Lae on 4-5 September removed all doubt that Finschhafen would soon be in the front line of combat. Eighteenth Army therefore immediately took additional steps to make the area as strong as possible within the limits of the supply and manpower situation. By this time the 20th Division had been relieved of its mission on the Madang-Lae road construction project and was ordered forward to reinforce Finschhafen. On 10 September the main body of the division65 under command of Lt. Gen. Shigeru Katagiri left the Bogadjim area in eighteen

[229]

march serials to move by overland routes to Finschhafen. By 21 September, however, the division, without horses or vehicles to facilitate its movement over the difficult trail, had only reached Gali and still had almost 100 miles to cover. The division actually was not scheduled to reach Finschhafen until 10 October. In the event of a prior enemy attack, Eighteenth Army hoped that the Yamada force, which had ample time to organize the ground, would be able to hold the Satelberg area, so that when the 20th Division main body arrived, it could be assembled for an immediate counterattack.

At dawn 22 September, a large enemy convoy appeared off Point Arndt and after heavy air preparation commenced troop landings. Maj. Gen. Yamada immediately issued orders for the concentration of his main force on Satelberg Hill to prepare for counteroffensive action. The 3d Battalion, 80th Infantry was dispatched as a sortie force to attack the enemy beach and reconnoiter the front in preparation for a fullscale counterattack.

At this critical moment much depended on the rapidity with which Japanese air units could mount large-scale attacks against the enemy amphibious forces. The 7th Air Division, though charged with this responsibility, was under orders to fly cover for a convoy inbound to Wewak on 23 September66 and hesitated to go out in force against Finschhafen, leaving the convoy unprotected. Fourth Air Army quickly ended this indecision by ordering the division to attack the Finschhafen landings, but bad weather prevented missions on the 23d and 24th. Meanwhile, however, planes of the Eleventh Air Fleet, flying from Rabaul, were able to take off and conducted heavy strikes on 22, 24 and 26 September against enemy shipping in the Finschhafen area.

Upon receiving confirmation of the enemy landing in the Point Arndt area, Lt. Gen. Adachi, aware that the success or failure of the defense of Finschhafen area would decisively influence the fate of the Dampier Strait region, ordered the Yamada force to launch an immediate attack against the enemy beachhead. (Plate No. 58) Meanwhile, the 20th Division began a race with time across the mountain trails from Gali to Finschhafen.

At Finschhafen Maj. Gen. Yamada and his small force faced a difficult situation. A force of approximately 1,000 enemy troops was approaching the north bank of the Mape River,67 and at Point Arndt a follow-up convoy was landing an estimated 5,000-6,000 additional troops with tanks and heavy artillery.68 On 26 September, another force of approximately 500 enemy troops, which had advanced along the coast from the Hopoi landing area east of Lae, appeared in the vicinity of Cape Cretin, six miles south of Finschhafen. Air support of the Yamada Force was meanwhile limited to two Army aircraft a day. The enemy had already overrun the Finschhafen airstrip and was preparing it for use.69

Pursuant to Eighteenth Army orders, the Yamada Force on 26 September launched a

[230]

PLATE NO. 58

Operations in Finschhafen Area, September-December 1943

[231]

coordinated attack from the Satelberg Hill area in the direction of Heldsbach Plantation, the 80th Infantry Regiment in the assault. The objective was to reduce the enemy beachhead before further reinforcements could be brought ashore. A heavy engagement ensued in the area between Satelberg and the sea. Meanwhile, in Finschhafen, the naval garrison of about 300 men and a company of the 2d Battalion, 238th Infantry, comprising the defense force of the town, were surrounded on 27 September. This force withstood five days of ferocious enemy attack but was finally overwhelmed on 2 October. With the fall of Finschhafen, the Allied force could now turn its full attention to the main strength of the Yamada force operating east of Satelberg. The attack of the 80th Infantry had been halted short of its goal, and the regiment, now on the defensive, was engaged in heavy fighting in the vicinity of Satelberg Hill. During this period the enemy began using the Finschhafen airstrip.

On the morning of 11 October, the command post of the 20th Division was established on Satelberg Hill, and Lt. Gen. Shigeru Katagiri took command of all forces in the Finschhafen area. After four days spent in assembling the newly arrived troops, the division launched a surprise attack early in the morning of 16 October through Jivevaning in the direction of Katika. After heavy fighting, the enemy force was cut squarely in two, and 20th Division units reached the sea at Katika the next day. On the same day, 17 October, the Sugino Boat Unit landed in the enemy rear at Point Arndt and threw the opposing forces into disorder.70

The situation was now highly favorable. As a result of the successes of 16-17 October, the 79th Infantry Regiment swarmed along the coast in full force, overrunning enemy positions and capturing large quantities of weapons and ammunition, as well as trucks fully loaded with rations and medical supplies. Prospects for the early recapture of Finschhafen were momentarily bright. However, in the Heldsbach area, the enemy line suddenly stiffened, and the regiment was forced to deploy. On 20 October the Allied force was reinforced from the sea,71 and a new and ferocious battle ensued around Point Arndt. Since neither side seemed to be able to break the deadlock, the fighting temporarily slackened while both sides prepared new blows.

Because of the supply situation, Lt. Gen. Katagiri recognized the importance of quickly reorganizing his units and resuming the attack in order to gain a quick decision. On 31 October the Army Commander, Lt. Gen. Adachi, arrived at the 20th Division command post and studied the situation. Enemy strength was estimated at one division, confronting the Japanese forces along a winding front extending from the north bank of the Song River south to Logaweng Hill via Jivevaning.72 Lt. Gen. Adachi ordered a renewal of the attack with the objective of seizing the mouth of the Song River in a series of limited objective operations. In order to prevent enemy landings in the Japanese rear, the 2d Battalion, 79th Infantry was dispatched north on 6 November under orders to reconnoiter as far as Lakona and strengthen coastal defenses. Meanwhile, although the division was on one-third rations and short of

[232]

ammunition,73 Lt. Gen. Katagiri set the date for the new attack at 23 November.

While the 20th Division was preparing its new assault, the Allied forces were pouring ashore reinforcements and supplies.74 On 16 November, a full week before the scheduled attack date, a coordinated enemy drive supported by a large-scale air strike was launched against the Satelberg position. The struggle that followed was one of the heaviest battles fought in the southeast area. Units of the 6th Air Division turned out in force and gave unusually heavy support to the ground effort.75 Beginning on 23 November, heavy meeting engagements developed north of the Song River as the Allied force drove toward Bonga and Wareo. On Satelberg Hill, the 80th Infantry, which had been subjected to ten days of sustained air and ground attack, terminated its heroic defense on 26 November and withdrew beyond Wareo on division order. In spite of its failing troop strength and scanty store of provisions, the 20th Division on 30 November launched a counterattack to ease the pressure on Wareo and Bonga. This desperate attempt failed, and on 8 December, under renewed enemy assaults, Wareo fell. A week later the enemy entered Lakona after shattering the determined resistance of the 79th Infantry.

It was now clear that the Finschhafen base was irretrievably lost and that the 20th Division lacked sufficient combat strength to renew the offensive.76 Accordingly, on 17 December, pursuant to directives from General Imamura at Rabaul, Eighteenth Army ordered the division to withdraw behind the Mesaweng River, adopt delaying tactics, and hold out in the Sio area.77 The retirement behind the Mesaweng began on the night of 19 December. Along the coast, the 2d Battalion, 79th Infantry, conducted delaying actions on successive positions all the way from Wandokai to Kalasa. The main body of the 20th Division closed into Kalasa on 29 December.78 Thus, in two and a half months, the opening battle in the defense of the Dampier Strait had resulted in disaster.

While the 20th Division was still conducting its gallant but unsuccessful defense of the

[233]

west coast of the Dampier Strait, the enemy forces in the Solomons again unleashed a new assault. This time the target was Bougainville, left flank strongpoint of the Eighth Area Army line and strategic key to Rabaul.

Following determination of the new national defense zone at the end of September, Eighth Area Army had notified Lt. Gen. Haruyoshi Hyakutake, Seventeenth Army Commander, on 7 October that the army's primary mission was to organize and strengthen the defenses of Bougainville. Under this directive Lt. Gen. Hyakutake immediately concluded a local operational agreement with the Eighth Fleet, formulating joint plans to meet an eventual enemy landing in the Bougainville area.

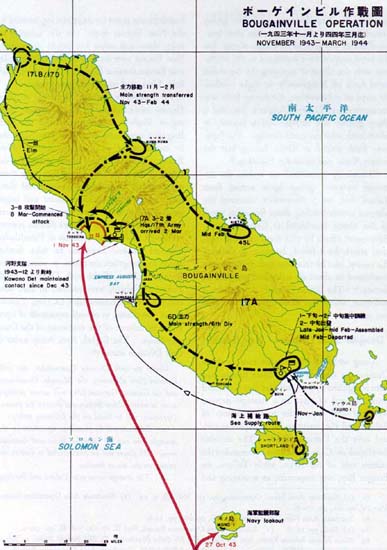

Execution of these plans had barely gotten under way when, on 27 October, enemy forces landed on Mono Island, due south of Bougainville, and five days later followed up with the main landing effort in the Cape Torokina area, on the northern side of Empress Augusta Bay. (Plate No. 59) Since the terrain on the western side of Bougainville was so low and damp as to render it relatively unsuitable for attack operations, Seventeenth Army had not anticipated a landing in the Empress Augusta Bay area, and the only force there was a small observation unit.79 This was speedily overwhelmed, and the enemy began a slow advance inland.

The command post of the Seventeenth Army and the bulk of the forces on Bougainville were at this time in the Erventa area, on the southeast tip of the island.80 Here, they were disposed to cover the shores of Tonolei Harbor and the Buin area, where the Navy had a base and also the largest operational airfield in the Solomons.

Confronted by the enemy landing on Empress Augusta Bay, Lt. Gen. Hyakutake immediately dispatched the 23d Infantry Regiment (less 1st Battalion) of the 6th Division to the Torokina area by overland routes.81 Meanwhile, the 2d Battalion of the 54th Infantry Regiment, 17th Division, which had arrived at Rabaul, was ordered to undertake an amphibious operation directly against the enemy beachhead. The Eleventh Air Fleet, newly reinforced by 173 carrier-based aircraft, prepared to render strong support to these operations.

While the 23d Infantry moved overland toward Empress Augusta Bay, six destroyers carrying the 2d Battalion, 54th Infantry sailed from Rabaul on 2 November, covered by a naval support force of four cruisers and six

[234]

PLATE NO. 59

Bougainville Operation, November 1943-March 1944

[235]

destroyers.82 The destroyer transport group turned back when the convoy, soon after leaving Rabaul, was spotted by enemy planes, but the naval support force continued to the southeast with the object of engaging the American naval force off Bougainville in night combat. At 0050 on 2 November, the enemy force was encountered off Empress Augusta Bay, and a sharp gunfire and torpedo action ensued, in which both sides sustained damage. The Japanese force retired at dawn, having lost the cruiser Sendai and destroyer Hatsukaze.83

Covered by intensified air action, the destroyer transport group again sortied from Rabaul and, on 7 November, executed the planned counterlanding about five miles north of the enemy beachhead at Cape Torokina. Subsequent efforts by this force and the overland attack force failed, however, to dislodge the enemy, who by this time had deepened the beachhead to about six miles and prepared an airstrip.84 The action settled down into a stalemate, which was to continue for the next five months.

Dampier Strait Defense: New Britain

Along with the Finschhafen area on New Guinea, the western end of New Britain had been recognized by the southeast area command since the end of 1942 as a strategic defense sector of vital importance to the security of Rabaul and the maintenance of Japanese control over the Dampier Strait. The airfields developed on Cape Gloucester commanded the eastern side of the strait, while Tuluvu, on Borgen Bay, was important as a staging and transhipment point for units moving forward to the New Guinea front. In the summer of 1943, these and other key points on western New Britain were secured by the 65th Brigade, 51st Reconnaissance Regiment, one Naval Garrison Unit, and various shipping units.

In September, as the fighting in New Guinea moved closer to the Dampier Strait region, Eighth Area Army placed the 65th Brigade Commander, Maj. Gen. Iwao Matsuda, in command of all forces in western New Britain and ordered him to strengthen the defenses of the area. In compliance with these orders, Maj. Gen. Matsuda organized these forces as the Matsuda Detachment and began welding the widely-scattered garrisons in western New Britain into a cohesive defense system.

On 5 October, the situation at Finschhafen impelled General Imamura to take further action to strengthen the forces in western New Britain. Units of the 17th Division, newly arrived at Rabaul, were ordered to that area, and the division commander, Lt. Gen. Yasushi Sakai, was placed in overall command of operations in defense of the east coast of the Dampier Strait. The Eighth Area Army order to 17th Division stated:85

Under the 17th Division Commander, the 17th Division (less elements), the Matsuda Detachment and the Gasmata Garrison Unit will secure strategic areas in western New Britain and destroy the enemy. Operations will be based on the following policy:

1. Emphasis will be placed on operations in the strategic area east of Dampier Strait and Gasmata area. All forces will be concentrated to destroy the enemy on the sea or beaches.

2. The strategic areas near Tuluvu and Busching

[236]

will be secured to destroy the enemy.

3. Gasmata will be garrisoned with three infantry acid one field artillery battalions. Cape Merkus will be secured with one infantry battalion. Transportation and supply facilities in the rear areas and on the sea will be maintained.

Detailed defense plans elaborated on the basis of this order called for the disposition of forces at key points, chiefly Talasea, Borgen Bay-Cape Gloucester, Busching, Cape Merkus, and Gasmata. Owing to jungle and mountain barriers as formidable as those on New Guinea, the deployment of troops to these areas had to be carried out by water movement under the constant menace of enemy air attack. The main lift for units of the 17th Division was provided by destroyers and landing barges, using the night transport methods instituted in the spring of 1943. Although these movements were accomplished, the maintenance of supply lines to the western outposts remained a serious problem.

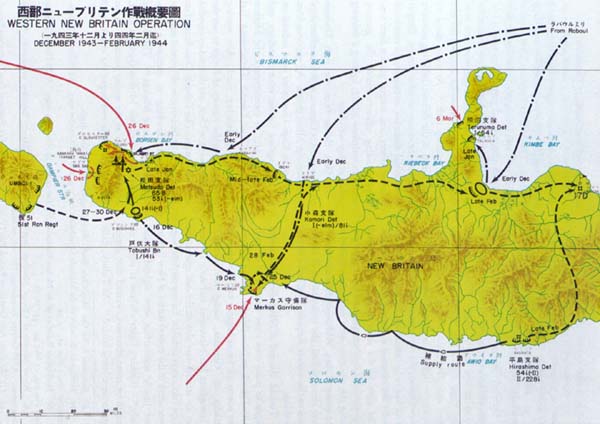

Toward the end of November, indications began to point even more strongly to an early Allied attack on New Britain. On 20 November enemy air forces began a two-day series of attacks on Gasmata, using 100 aircraft.86 Throughout late November and early December air attacks were also accelerated against the Cape Gloucester airfields. Enemy torpedo boats were active in the coastal waters of New Britain, and hostile submarines were sighted almost daily.87 Blinking lights offshore at night, reported by coast observers, warned that enemy agents were being landed.88 At Tuluvu, daily air raids continued until 17 December.

At 0200 15 December, a naval seaplane on routine reconnaissance reported sighting a small enemy amphibious convoy standing into Cape Merkus. The Merkus Garrison Unit, consisting of only two companies, immediately went to battle stations and prepared to meet a landing. (Plate No. 60) As the enemy formations approached the shore, the garrison force took them under heavy automatic weapons fire and sank 13 landing craft.89 At dawn naval air units joined in the defense, inflicting extensive damage on the enemy invasion convoy. Despite these initial successes, enemy troops continued to come ashore, and intense gunfire from warships standing offshore forced the garrison troops to withdraw inland, fighting a delaying action as they withdrew.

Lt. Gen. Sakai, from the 17th Division command post at Gavuvu, took immediate steps to counter the Allied thrust. All garrisons from Gasmata to Cape Gloucester were ordered on the alert against further enemy landings, and plans were laid to counterattack the Merkus beachhead. The Komori Detachment (1st Battalion, 81st Infantry, reinf.) then moving overland from the vicinity of Kirige to join the Merkus Garrison Unit, was directed to expedite their movement. The Tobushi Detachment (1st Battalion, 141st Infantry, reinf.) moved amphibiously from Busching to execute a counterlanding on Cape Merkus.90 The Komori Detachment, with the Merkus Garrison Unit, advanced as far as the enemy positions on the Merkus Peninsula and began the attack on 28

[237]

PLATE NO. 60

Western New Britain Operation, December 1943-February 1944

[238]

December. On the following day, the Tobushi Detachment joined the Komori Detachment and futile attacks were repeated for several days but all efforts fallen.91 Throughout this period naval air units operating from Rabaul and 6th Air Division planes operating chiefly from Wewak carried out repeated assaults on the enemy ships supplying the beachhead, inflicting substantial damage but also taking severe aircraft losses.92

Lt. Gen. Sakai estimated that the Merkus landing was not the main enemy effort, and his suspicions were soon confirmed. From 19 December, Japanese positions on and around Cape Gloucester were subjected to heavy daily air attack. On 20 December a reconnaissance plane reported that a large concentration of enemy transports and other assault shipping had rendezvoused in Buna Bay.93 On 25 December a large enemy convoy was spotted moving northward in the direction of Dampier Strait, and the Matsuda Detachment, responsible for the defense of the Borgen Bay-Cape Gloucester area, was promptly ordered to battle stations.

At 0400 on 26 December, the defenses skirting the Cape Gloucester airfield and Silimati Point were subjected to devastating naval gunfire preparation, followed by heavy air strikes. At dawn enemy troops began landing at two points, the main force going ashore northwest of Silimati Point and a smaller contingent debarking just west of the Cape Gloucester airfield.94 Maj. Gen. Matsuda immediately began deploying his troops to meet this two-pronged attack, which obviously aimed at the encirclement of the airfield area. The nearest unit to the main enemy landing was the 2d Battalion, 53d Infantry, which was quickly ordered to launch local counterattacks pending commitment of the main strength.

On the morning of the landings, naval air units from Rabaul and Kavieng went out in strength to smash the enemy convoy. Hostile fighter cover over the beach was so thick, however, that the results were inconclusive, although the enemy's transport formation was dispersed. At twilight the attack was renewed with more success, several enemy ships receiving heavy damage. Japanese plane losses in these and subsequent operations, the air raids on Rabaul, and the appearance of enemy carriers in the waters east of New Ireland prevented the naval air units from carrying out further operations. By early January the number of serviceable aircraft other than fighters available for operations in New Britain had dwindled to approximately 24 navy medium attack planes, 8 navy bombers, and no army bombers at all.95 From this time on, the air forces were unable to influence the decision at Cape Gloucester.

On the ground, fierce fighting took place for possession of the airfield area. Every effort to defend this locality by the Matsuda Detachment proved unavailing, and the detachment was forced to evacuate its positions. Maj. Gen. Matsuda, however, had concentrated his main strength, consisting of the 53d, 141st Infantry and the 51st Reconnaissance Regiments, on commanding ground in the area southwest of

[239]

Silimati Point. Though cut off from all reinforcement and supply, and with no air support and very little artillery, this force on 3 January launched a counterattack against the American troops advancing along the west side of Borgen Bay and succeeded in carrying Sankaku Yama96, a prominent terrain feature overlooking the beach. The hill could not be held, however, due to mass enemy artillery fire and air bombardment, and the Japanese were forced to withdraw.

After this effort failed, further resistance on Cape Gloucester was out of the question, and the Matsuda Detachment was ordered to withdraw toward Talasea. The Dampier Strait campaign thus ended on 24 January 1944, four months after the opening gun was fired at Finschhafen. The main route of advance to the national defense zone in Western New Guinea now lay open to the enemy.

The situation which confronted the Eighteenth Army at the end of 1943 was dark indeed. The bitter loss of Finschhafen, coupled with the enemy advance into the upper Ramu Valley, had virtually opened the way for an assault by General MacArthur's forces on the nerve-center of Eighteenth Army resistance at Madang. Sio, on the northeast corner of the Huon Peninsula, remained the only important defense area between Madang and the enemy forces driving up the coast from Finschhafen. At Sio, the 20th Division, seriously weakened in the Finschhafen campaign, was reassembling its depleted forces in preparation for a new defensive stand. The 51st Division, consisting largely of combat ineffectives, was also spread out to the west of Sio waiting to move to the rear for rest and refitting.97

The enemy was not slow to take advantage of this favorable situation. Striking swiftly in a new amphibious operation, Allied forces on the morning of 2 January 1944 landed in the vicinity of Saidor, about halfway between Sio and Madang.98 (Plate No. 61) Eighteenth Army, although it had feared a new enemy landing somewhere along the north coast of the Huon Peninsula,99 was powerless to combat it. With the enemy at Saidor, the Army strength was split squarely in two, and two exhausted, understrength divisions were cut off in the Sio Area.

In view of the weakened condition of these units and the urgent need of bolstering the thin defenses of Madang, the Eighth Area Army headquarters in Rabaul relieved the Eighteenth Army Commander of further defense of the Sio area. The Eighteenth Army Commander, who was then at Sio, directed their withdrawal past the Saidor beachhead to the Madang area.

In compliance with the Area Army order, Lt. Gen. Adachi ordered the 20th and 51st Divisions to proceed as quickly as possible to the Madang area, and placed Lt. Gen. Nakano, Commander of the 51st Division, in over-all command of forces east of Biliau, including the 20th Division. Lt. Gen. Adachi then left by submarine for Madang, where the 41st Divi

[240]

sion, moved forward from Wewak, was charged with organizing the defenses of the area pending the arrival of the 20th and 51st Divisions.

Lt. Gen. Nakano now tackled the problem of evacuating his command past the expanding enemy beachhead at Saidor. Two routes were chosen, one running fairly close to the coast and the other following the ridge-line of the Finisterre foothills.100 The 20th Division was to take the coastal route, while the 51st, together with some naval units, was to use the route inland. The first echelon was scheduled to reach Madang on 8 February, and the entire movement was to be completed by 23 February. To divert the enemy at Saidor, eight infantry companies of the Nakai Detachment, under command of Maj. Gen. Nakai, were ordered to withdraw from the Ramu Valley front and advance: down the coast from Bogadjim to threaten the enemy beachhead.101

The first echelon of the retiring 20th and 51st Division forces left Sio on schedule. At the last minute, however, the withdrawal plan was modified in favor of moving both divisions via the inland route. The covering operations of the Nakai force were carried out according to plan, and the Nakano group successfully negotiated the withdrawal without encountering enemy resistance. Illness and starvation, however, took a heavy toll along the difficult retreat route. At the end of December the combined strength of the 20th and 51st Divisions had been about 14,000. About 9,300 finally reached Madang by 1 March.102

While the withdrawal was in progress, the Nakai force engaged the American troops attempting to break out of the Saidor beachhead toward Madang. To forestall this move, the force deployed along the Mot River line in the vicinity of Maibang and Gabumi. Enemy attempts to cross the river, although supported by heavy artillery fire, were repelled, and the line held firm until 21 February when the force, having completed its mission of covering the Nakano group withdrawal, retired to Bogadjim.

On the Ramu front, the enemy had meanwhile taken advantage of the reduced strength of the Japanese forces. On 19 January, the Australians, operating out of Dumpu, launched a determined attack on the Kankirei positions and, by 27 January, took possession of Kankirei. The Nakai force returned to Bogadjim just in time to bolster the line and prevent the Australians from advancing down the Mintjim River to join forces with the Americans coming up from Saidor.

Madang was now extremely vulnerable to attack. The condition of Japanese air units did not permit reliance on air power to protect the town. The 41st Division and the Nakai Detachment were forced to spread their strength from the Finisterre Mountains to Astrolabe Bay and up through Alexishafen to Mugil. Thus dispersed, these units could not give adequate protection to Madang, even with the cooperation of the Ninth Fleet.103 The tide of

[241]

PLATE NO. 61

Ramu Valley and Saidor Operations, December 1943-February 1944

[242]

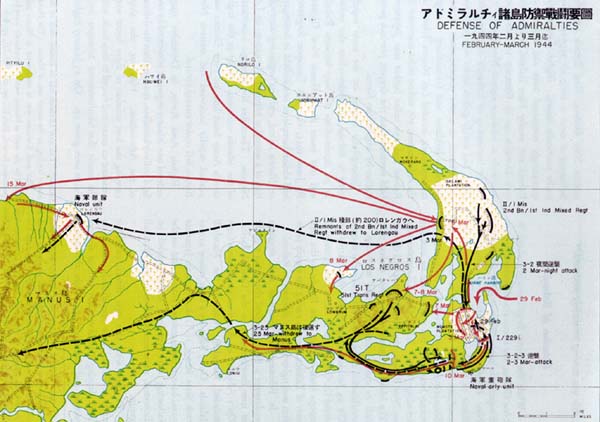

PLATE NO. 62

Defense of Admiralities, February-March 1944

[243]

battle was moving irresistibly westward.104

While the enemy forged steadily ahead in New Guinea, his forces already entrenched on Bougainville in the Solomons and on western New Britain itself created an ever-growing threat to the heart of Japanese power in the southeast area at Rabaul. On Bougainville, Seventeenth Army succeeded in containing the enemy beachhead but was unable to oust the invading forces. In the Cape Gloucester area on New Britain, the situation was still darker. The Matsuda Detachment, down to less than half its combat strength, faced starvation or annihilation at the hands of the superior enemy. On 23 January 1944, Eighth Area Army ordered Lt. Gen. Sakai to move immediately all troops from western New Britain to the area east of Talasea, thereby easing the supply problem and tightening the defenses of Rabaul.

In February the southeast area situation underwent a further radical change as a result of new developments in the Central Pacific. On 1 February an American amphibious force invaded Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands. On 17 February a large enemy carrier task force struck at Truk, the main Japanese naval base in the mandated islands, and on the following day American troops landed on Eniwetok, westernmost island in the Marshall group.

To cope with this new threat, naval air units at Rabaul were immediately ordered to Truk, leaving Rabaul virtually without air protection and depriving the forces throughout eastern New Guinea, New Britain and the Solomons of most of their air support. Sea traffic practically ceased. Eighth Area Army, increasingly concerned over the defense of Rabaul and nearby New Ireland, ordered the 17th Division on 23 February to move immediately to reinforce eastern New Britain.105

The buttressing of Rabaul's shrinking defenses had barely gotten under way when the Allied forces, in a new surprise move of consummate boldness and far-reaching strategic consequences, invaded Los Negros Island, in the Admiralties, 365 airline miles northwest of Rabaul and 250 miles farther into Japaneseheld territory than the deepest previous penetration by amphibious forces.

Strategically located on the main supply route to Rabaul, the Admiralties also served as an intermediate air stop between Rabaul and rear bases in Northeast New Guinea. By June 1943, the 51st Transport Regiment had almost completed one airfield at Lorengau, on Manus Island, and was beginning construction of a second at Momote Plantation, on Los Negros. Thereafter the strategic importance of the islands increased steadily as the Eighteenth Army front line on New Guinea was pushed rapidly backward and western New Britain fell under enemy control.

Eighth Area Army, in December 1943, ordered one infantry regiment reinforced by one field artillery battalion, to strengthen the defense of the Admiralties. However, the ships carrying the first echelon of these forces were attacked en route and forced to turn back, with the result that reinforcement attempts from Palau were given up. On 23 January Eighth

[244]

Area Army ordered the 2d Battalion of the 1st Independent Mixed Infantry Regiment, stationed on New Ireland, to move to the Admiralties. A week later the 1st Battalion, 229th Infantry, 38th Division was also ordered to proceed from Rabaul to the Admiralties by destroyer. All forces in the Admiralties were placed under Col. Yoshio Ezaki, 51st Transport Regiment commander, with the missions of securing Los Negros Island with its vital airfield106, and preventing the enemy from seizing and establishing airfields on Manus, Pak and Pityilu Islands. Fourth Air Army was to cooperate in the defense of the Admiralties in the event of an enemy landing attempt.107

Defensive dispositions in the Admiralties were based on the anticipation that an Allied landing attempt would probably be made somewhere along the shore of Seeadler Harbor or the eastern and southern shores of Los Negros. (Plate No. 62) Hyane Harbor, on the opposite side of Los Negros, was not considered a likely landing point due to its smallness and the danger to which enemy movement through the narrow harbor entrance would be subject.

The defending forces on Los Negros were taken by surprise, therefore, when a small enemy invasion force, following a brief but intense naval gunfire preparation, began landing on beaches inside Hyane Harbor at 0815 on 29 February, striking directly at Momote airfield. The 1st Battalion, 229th Infantry, defending the airfield sector, was slow in reacting but, on the night of the 29th, launched a counterattack which failed to dislodge the beachhead. On 1 March a small number of aircraft attempted to support the ground defense but were driven off by strong enemy air cover. A further counterattack launched at 1700 the same day was broken up by enemy artillery.

On 2 March the enemy, heavily reinforced from the sea, gained possession of the airfield. Col. Ezaki now planned a pincers attack from north and south, ordering the 2d Battalion, 1st Independent Mixed Infantry Regiment to attack from the Salami Plantation area, north of Hyane Harbor, in conjunction with a further counterattack by the 1st Battalion, 229th Infantry, from the southern sector. The attack was to be launched on the night of 2 March, but due to heavy enemy air and naval bombardments, it had to be delayed.

Spearheaded by the 2d Battalion, 1st Independent Mixed Infantry, the main attack was finally launched on the night of 2 March. The enemy positions were successfully infiltrated, but the curtain of mortar and artillery fire encountered by the 2d Battalion was so intense that its gains could not be exploited. This abortive attack was the last large-scale effort which the Japanese forces in the Admiralties were able to mount. Thereafter, although fighting continued on Los Negros until 12 March and on Manus until early April, the outcome was inevitable.

With the Admiralties in their grasp, the Allied forces were now squarely astride Eighth Area Army supply lines and in a position to isolate the large numbers of Japanese troops remaining on New Britain, New Ireland and

[245]

in the Solomons. They were also in possession of a base from which further amphibious attacks might be mounted against Japanese rear bases on New Guinea. Such an attack was anticipated about the end of April.108

While the Admiralties campaign was in progress far to the rear, the Seventeenth Army on Bougainville launched, the last large-scale Japanese offensive effort in the Solomons in an attempt to wipe out the enemy beachhead in the Empress Augusta Bay area.

On 21 January, the Eighth Area Army Commander, General Imamura, flew from Rabaul to Bougainville and set early March as the target day for the attack. In midFebruary Lt. Gen. Hyakutake, Seventeenth Army Commander, conducted extensive reconnaissance of the enemy front and began assembling his forces for the offensive. Training had been tough and thorough, and the assault units moved overland from their bases confident of victory.